Originally published in The West Asheville News – Holiday 2003, Volume 1, Issue 4

by Reid Chapman

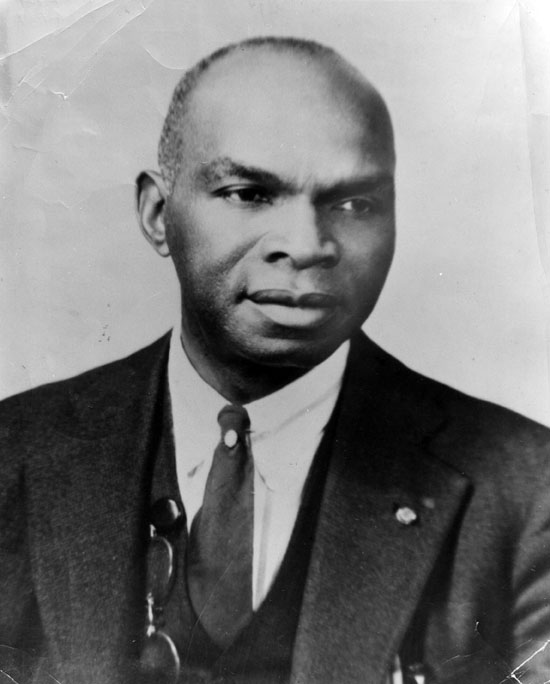

To visit John Bell’s shop-cum-museum is to sit at his feet for a moment. In that moment he offers lessons on relationships, work, and life in general. And he’ll drop a string of names on a listener—not to impress, but to communicate where he comes from. As he puts it, “This ain’t all about me.”

John Bell was born in 1939 in the old Mission Hospital. He lived on Mitchell Avenue in West Asheville for the next 25 years. He credits his childhood friend Sid Parker with pointing out that he grew up in an “Ozzie and Harriet family.” During the Second World War, he made the rounds of the neighborhood with his father, an air raid warden, checking to make sure all the lights were out. He had the freedom to ride his scooter to the A & P grocery store. His was a neighborhood in which “lots of people had influences on kids.” He cited George Prosser, a relocated Englishman, with teaching him “how to go out to the woods and see something other than trees.” In those days, he says, “You didn’t worry about people stealing.” The worst thing he could think to say about his childhood home was walking out on a Sunday morning and passing Lavonne’s, the drive-in that is now Franklin’s Outdoor Sports, and seeing the white gravel thrown out in Haywood Road the previous evening by cars peeling out of the lot.

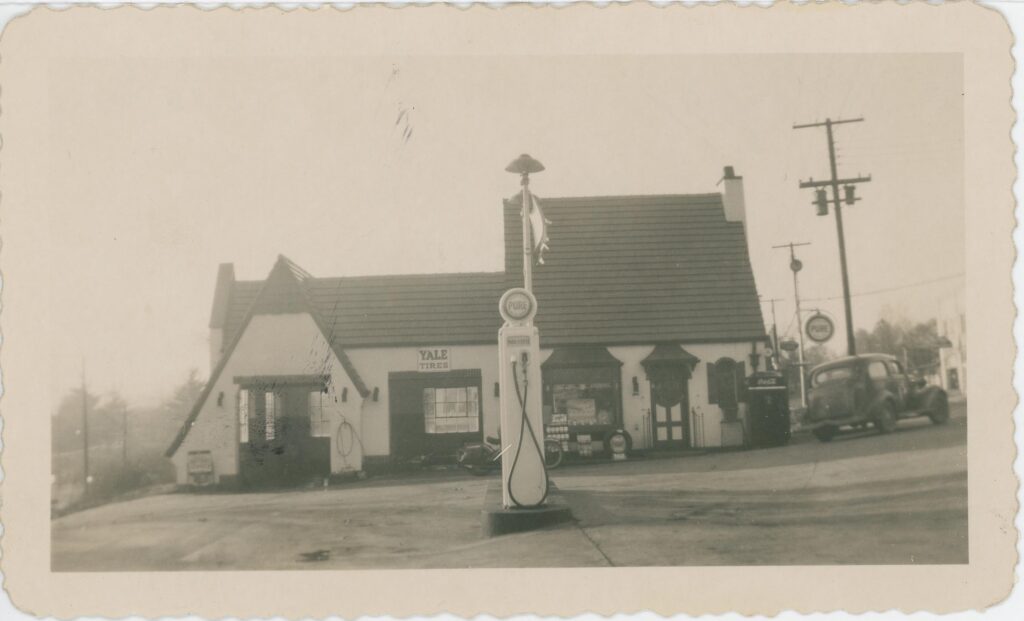

John’s lifelong love of racing began in 1953 with his first soap box derby raced along South French Broad Avenue. His interest in cars goes back even farther. His childhood is filled with the lore of automotive travel. In 1926, his father and three other West Asheville boys drove a $15 Model T Ford across the United States

When Bell graduated from Lee Edwards High School in 1957, his dad issued a warning: “You’re not going to sit around all summer. Either go to college or join the service.” John reflected that “I’d had about enough of school at that point,” so he joined the Army. He quickly learned the difference between the geniality of West Asheville and the reality of the larger world: “I didn’t know about the rest of the things going on until 1957.” He spent the next three years in France.

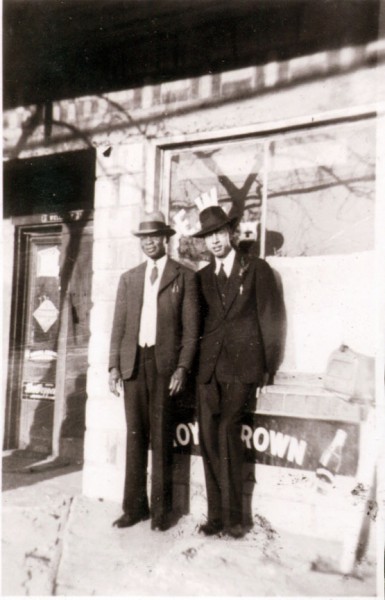

In 1962, a few years after John returned from the service, his father bought Main Auto Parts on Craven Street behind the stockyard. Bell proudly walks any interested parties through the shop, showing off photographs and artifacts documenting the history of the business. The building was built in 1947, replacing a smaller one. At that time the company bought old cars and other scrap metal. He shows off the award given the business by the War Department during the Korean War for contributing scrap metal to the war effort. “830 tons ain’t a big deal till you realize they’re doing it by hand.” At that point in time cars were scrapped and hauled down to the rail line over a half mile away. “I was 21 years old when I first walked through that door. It’s hard to look at this stuff and realize 40 years of your life has gone by.”

Bell began closely following racing during this time, often working in the shops of racers Banjo Mathews and Roy Trantham. He also went to the races down at the Speedway “‘bout all the time.” He took particular interest in a young Randy Bethea, encouraging his attraction to racing. Bethea went on to become the first and only Black NASCAR driver to win a Busch series pole. In 1963, Bell met Patricia Allen at a car show. He reports that she said, “If you need anybody to polish your trophies, give me a call.” They were married two years later. Shortly thereafter, with a wife, a house, a business, and two girls to raise, “there was no time for racing.” Bell took to working on “show” cars, taking them to Charlotte and Greensboro.

He has an obvious pride in his family, taking the opportunity to describe the achievements of his daughters, Leslie and Shannon. He commented on the recent pleasure of getting to watch his grandson take his first step. This experience was made all the greater knowing that his father had watched his daughter Shannon take her first step. Such traditions are important to John Bell. Later, while looking over Bell’s soap box race car, I asked if that same grandson would have the opportunity to race it. Bell replied that it would be better for his grandson to build his own. “That thing about making it easier for your kid than you is a myth. They’ll take it for granted.”

John’s life took an interesting turn three years ago, when he began to draw social security. He looked at that first check and realized it would just about fund a racing hobby. He took to running local dirt tracks. He proudly comments, “I’ve got the only federally funded car in the circuit.” He doesn’t miss the irony of this transformation either. “The guys who were racing when I started fixing cars are now burnt out on racing and are working on cars now that I’m racing.” And he’s had a good bit of success as well. In the past three years he has won three heat races and one feature race. His friend John McRealth got him back into racing. Although they both have cars, they work often as a team. In one recent race McRealth “tore his car up, and I gave him mine.” McRealth went on to win the race, and Bell went on to earn an award for sportsmanship. As Bell reflected to his friend, “John, that sportsmanship award might mean more to me than a first place.” This fits right in with another of Bell’s philosophies: “You only get out of life what you give away.”

John Bell with his 1953 soapbox derby entry. Photograph by Reid Chapman.